Reclaimed Cladding Part 1

All steel is recycled. It has been since long before recycling was a thing. And this idea, this ability to forge one object into another, has captivated the human imagination for ages. From “swords into plowshares” to the custom knives that I and other craftsmen make from recycled materials, we are inspired by the promise of alchemy.

Yet every steel object that you see in daily life, from a soup can to the golden gate bridge contains some atoms of iron that were perhaps once a Crusaders sword, a nail in the deck of a ship bound for the New World, who knows, the school desk where your favorite author sat and penned their first prose.

Put in such dramatic and universal terms, its easy for the idea to lose meaning. If a butter knife at Denny’s is made from trace amounts of medieval armor who cares if I forge a blade from old wagon tires? Its true. There is nothing unique or novel about working with reclaimed materials. And envoking the former lives of the material can feel trite or overblown.

And yet there remains something so compelling about this sort of work. Perhaps this is precisely because it’s not new or original but ancient and deeply essential. The smith employs the fundamental ability of the metal to coalesce and gives new form and utility to something that was no longer useful. And this is the other joy (that promise of alchemy): taking what was discarded and making something not repaired or repurposed but entirely new.

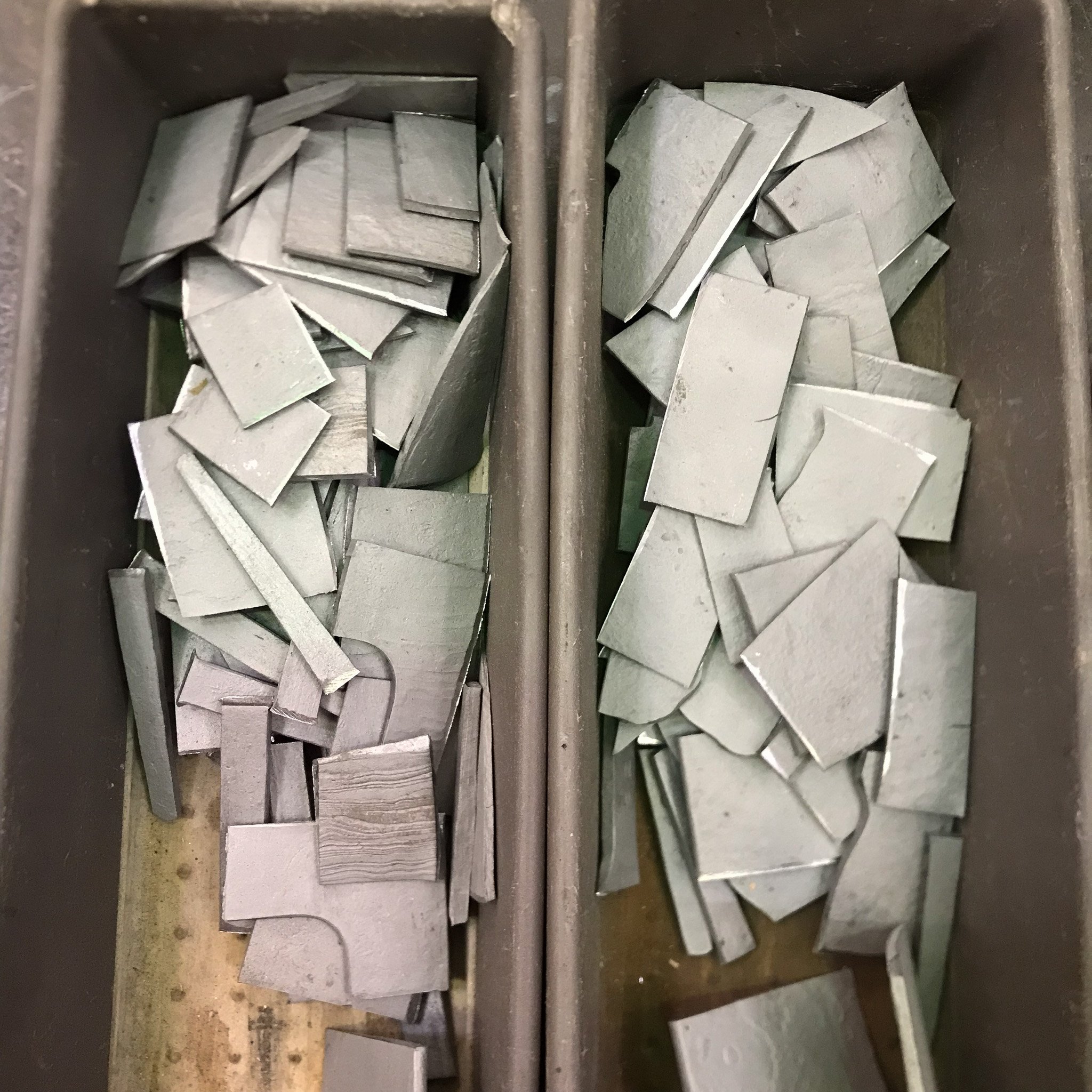

I have kept many (not all) of my failed knives over the years. And there are plenty. Some cracked during heat treatment or had voids in the welds, etc. All were unsalvageable, except by reforging. Here you see the first step of reclaiming this material: wrought iron clad knives are cut into pieces and cleaned.

The pieces are stacked up on a broken blade. Using the old tang as a handle, they are heated in the fire and forge welded. The block is cut in half and and the old tang removed.

I have found that its important to carefully select the pieces as they are assembled for a good blend of high and low carbon. Then the real challenge begins. If I fold this billet 3-4-5 times, I have very few problems with delamination or voids in the welding. However, because the knife shards already contained many thin layers, the material homogenizes dramatically (knife above left). I prefer the appearance of the blade on the right. But this requires only folding the billet once or twice, which increases the chances of flaws in the welding.

Because the material has been forge welded only the bare minimum, there are times when I see a dark spot on the surface on the steel indicating a pocket of delamination underneath. If the spot is small , I can try, as a desperate measure to pierce the bubble with a chisel and put a patch (made of a knife shard) over it. The two patches are highly visible in the left example. The photo on the right has a less noticeable patch over the spine, coming down into the grind just a little.

These features can be really beautiful. I have visions of making blades where the entire cladding is composed of overlapping piece, like a patchwork quilt. However, in reality its incredibly diffucult to do with these materials. Its a lesson in the way that, “planar arrays rotate and align during forging” as one reads in the literature. Even if not folded, when the amount of displacement during forging is significant, the pieces will no longer appear distinct and separate. There have also been times when the patch technique did NOT render a pleasant effect and instead produced an ugly smear.

For now, I plan to make one more batch of experimental blades with these materials. Its possible they will all end up back in that box of failed knives (many from these experiments already have). Regardless of any of that, it has been good to engage the material in this way; to look at that box of failures as valuable material and make use of its inherent capacity for pragmatism. And at moments maybe even allow myself to see in these layers, if not viking helmets and Benjamin Franklin’s fountain pen, at least the many years of my own work and many lessons learned along the way.